Three Dollar Bill

When I met Allan Berube in 1989, he told me that he had just written a book about the lives of gay people who had served in World War II. In “Coming Out Under Fire he states that many gays and lesbians enjoyed a surprising level of tolerance in the military at the beginning of the war. After a rapid mobilization of 2,500,000 troops in 1941, America needed all of the soldiers it could muster, so the top brass had more important things on their minds than dealing with a few homosexuals within their ranks.

So long as they were discreet, these men and women could meet in secret as an early version of don’t-ask-don’t-tell settled in. If caught in the act, they risked a dishonorable discharge. Worse yet, they could be sent to the stockade or a military hospital.

By the mid-1940’s, the Pentagon adopted a policy to ferret out gay soldiers, but many GI’s refused to turn in the “queers” who had bravely fought alongside them. As the war dragged on with no end in sight, enlisted men had few opportunities to be with women. Some curious (or just plain horny) guys figured that they were probably going to die anyway, so they indulged in a little surreptitious, man-on-man sex.

A lot of them stopped when they returned home. Some gay veterans settled on the coasts and sowed the seeds of future LGBTQ+ communities. Others went back to their home towns and carried on in the closet .

After suppressed memories of my father surfaced a few years ago, I began to wonder if PTSD was the only thing that he brought back with him from the war.

I grew up in University City, an upper-middle class suburb of St. Louis. The four-bedroom, brick-and-stucco house with large, south-facing bay windows was set back from the street by a sprawling lawn. A serpentine concrete pathway led from the sidewalk to the front door. A Ford sedan sat in the driveway in front of an attached garage. My older sister Barbie and I played in the back yard while Dad barbecued steaks on hot summer evenings.

From the outside, it was the picture of a prosperous, post-World War II American home. Behind its walls, Dad got drunk every night and when his blood-alcohol level reached a flash point, he conjured up his wartime demons. Since there wasn’t much help for PTSD in the 1950’s, he unleashed them on his family.

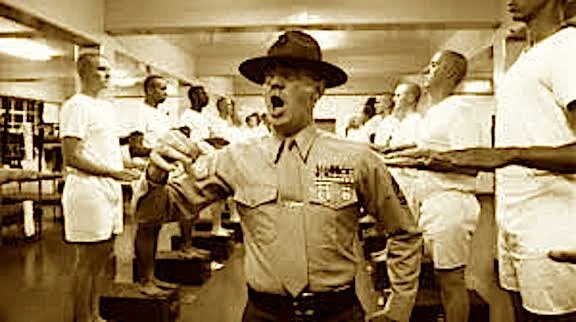

When he was really drunk, Dad told the story of a sergeant who had trained him in boot camp. He grew wistful as he talked about the small-framed, ultra-macho officer. While driving in an open jeep one day, he was decapitated by a wire strung between two trees.

Dad always wept at this part of the story. In the midst of his tears, he straightened his back and exclaimed:

“He was as queer as a three-dollar bill, but I loved him!”

Seeing Dad cry disturbed me. Hearing him proclaim love for a “queer” baffled me. Though I didn’t understand the exact meaning of the word, I was pretty sure that a “queer” couldn’t be a war hero. For Dad to say that he loved anyone was out of character. He didn’t say it to his kids and I only heard him say it to Mom a handful of times, usually after much wheedling on her part.

I never saw him ogle women in public, in fact he didn’t take much notice of them at all. He gave little attention to Mom and had no respect for her opinions. He dismissed anything she said by scowling “Aaaaach, goddamn women!” followed by a swipe of his hand that erased her words from the air.

Mom and Dad had cocktails in the living room every evening while we kids ate dinner in the breakfast room. When their arguments pierced the walls, I usually knocked over my glass of milk. When Barbie rushed back from the kitchen with paper towels, we sopped up the widening, white puddle and exchanged a heartsick glance.

The house crackled with tension as their fights escalated. They were always about the same thing: money.

Dad co-owned a small machine shop in the inner city that manufactured custom-made, metal products. No matter how drunk he got the night before, Dad always rose early, and threw on his oxford shirt, khakis and loafers. When the horn honked from the front curb, he downed a cup of black coffee and tore out of the front door to catch a ride to work with his business partner.

Mom openly disapproved of his career choice. All of her friends’ husbands dressed in suits and carried briefcases to downtown office buildings. She never missed a chance to denigrate Dad for not using the business degree that he had earned before the war.

“Why do you stay stuck in that filthy plant? Why don’t you get a real job?” she cried after a few drinks.

“Aaaaach, what have you got to complain about?” he yelled back. “I’m picking up the tab for everything so you can sit around all day!”

They went back and forth until Dad stormed out of the house to drink in dive bars with other men. After he left, Mom sank into a scotch bottle on the sofa and listened to her Frank Sinatra albums. Barbie went upstairs to her bedroom to distract herself watching television. Alone in my room without a record player or a TV, I bit my fingernails until they bled and spent hours banging my back against an armchair to tire myself out so that I could eventually go to sleep.

If there was a break in the sparring, and Dad was sufficiently worked up, he sometimes felt the need to pass his military training on to his children. While his beloved sergeant had made Dad into an efficient killing machine, he had neglected to install an off-switch.

Dad called Barbie (age ten) and me (age seven) into the living room and sat us on the couch.

“Oh not again!” Mom groaned from behind Dad’s back.

“Shut up! These kids have to know how to protect themselves,” he snarled without looking back, swatting her words away again like pesky flies.

She stared into her cocktail as Barbie and I sat wide-eyed on the sofa, our feet dangling over the plush carpet.

Dad staggered into the kitchen, crashed open the utensil drawer and burst back into the room brandishing a butcher knife. As he listed back and forth waving the blade, the rancid smell of his beer-breath stung my nostrils.

“Never hold a knife by the handle and stab a man,” he said jabbing at the air between us. “It can get stuck in the bones and tendons!”

His bloody imagery made me want to run upstairs, but I sat frozen in place.

“Oh, Ralph, stop it!” Mom protested. “You’re scaring them!”

“Quiet!” he barked not taking his eyes off us. “I’m trying to teach them something!”

Towering over us, he snaked his fingers up from the handle to the top of the blade.

“Hold it between your thumb and forefinger, just a few inches from the tip, and then slash the jugular!” he commanded, making a quick, horizontal motion from the back of his neck to the front of his throat and adding the word “Zzzzzzt” as a sound effect.

He curled lips into a satisfied smile and set the knife on the coffee table.

“Now I’m going to show you how to kill a man with three fingers!”

He must have figured this lesson would come in handy since neither Barbie nor I packed a knife in grade school.

He fashioned a menacing Boy Scout salute with his index, middle and fourth fingers, then curled them over his thumb to form a lethal mini-fist. He had me stand up and serve as The Enemy while he pointed out the sweet spot just below my not-yet-visible Adam’s apple.

“Aim right here and give it everything you’ve got!”

He bent down, rested his free wrist on my shoulder and steadied himself before drawing back his weaponized hand. In the ensuing seconds, I couldn’t look at his face and or close my eyes, so I fixed my gaze above his head and watched as my soul left my body. It hovered between his crewcut and the ceiling as he zoomed his hand towards my neck.

It always stopped a few inches short and I never flinched.

“And that’s how you kill a man with three fingers!” he announced.

He released my shoulder and I plopped back onto the sofa as my churning heart beckoned my spirit back into me. I looked over at Barbie, but she just stared straight ahead.

He scooped up the knife and lurched back into the kitchen. When we heard him toss it back into the drawer, Barbie and I took our first deep breaths. She grabbed my hand and we ran upstairs to our bedrooms.

Anyone could see that his training was wasted on his sissy-son. Whenever a bully approached me in the school yard, I cowered and ran away. Although thoroughly home-schooled in homicide, it never occurred to me to curl my little fingers around my thumb. Luckily for me, it wasn’t in my nature to go for the throat or I might still be in jail.

These drills were the closest Dad and I ever came to a father-son moment because he just wasn’t cut out to be a family man. He had no interest in staying home with the wife and kiddies when he could buy drinks for captive strangers in bars and regale them with his war stories. He was totally convinced that as long as he was providing me with food, shelter, clothing and an education, he had fulfilled all of his paternal obligations.

By the time I reached adolescence, I avoided my parents and went directly to my room after dinner. Inside of the safety of my bedroom, my fear of Dad hardened into contempt. I submerged any feelings for him in the same way that mean people drown kittens and I eventually forgot that I had ever cared about him at all.

I had outgrown my compulsion to bang against a chair, so I bought a radio. When the arguments started, I turned up the volume and concentrated on my homework. Dad never knocked on my door, he just followed his usual routine. He came home from work, took a nap, grabbed something to eat, got drunk, yelled at Mom and then blasted off to the bar.

At least, I thought he was at the bar.

I was back in St. Louis for the summer after my sophomore year at college. In the two years away from home, I had enjoyed many months outside of the family pressure-cooker and I was looking forward to my junior year in France. By the end of 1971, I had wholeheartedly embraced being gay and I was out to a few friends, but not my parents.

I went to bars every night and often didn’t return until morning. When I appeared home with a face ruddy with whisker-burn and a body reeking of sex, Mom and Dad were too busy nursing their hangovers to notice. On the rare occasions that they asked about my whereabouts, I told them that I had slept over at a friend’s house. They always swallowed the lie.

One evening, Mom and I were chatting over cocktails in the den when Dad materialized in the doorway. He planted his feet on the carpet and glared at me through bloodshot eyes.

“I just want to know one thing!” he growled.

He took a pause, but his theatrics no longer intimidated me. I just looked back at him through a haze of disinterest.

“Are you or are you not a homosexual?” he asked.

I shot back two simple words.

“I pass.”

My words could be taken one of two ways: “I’ll take a pass on answering that question” or “I pass as a heterosexual.”

I felt smugly safe inside my double-entendre since Dad had no sense of nuance. No match for him physically, I used my intellect to get the better of him and keep him farther away.

He swayed in the doorway for a few seconds, then gave his usual hand swipe.

“Aaaaach, that’s all right, I almost went that route myself!”

He turned on his heel and left the room.

“YOU WHAAAT?” Mom yelped as he beat a well-worn path to the kitchen windowsill to sneak another belt from the cobalt-blue glass full of vodka.

It was the glass that no one was supposed to know about. He officially sipped from his beer can in front of us, but went back and forth to the kitchen until he suddenly turned into a way-too-sloppy drunk. Everyone in the house knew about the blue glass, but we opted to collude in an age-old, alcoholic trade-off: I won’t call attention to your secrets, if you don’t mention mine.

In the wake of his quick exit, Dad’s words echoed in my head. They still do.

It never occurred to me to trail after him and ask what he meant. There were too many barriers between us that I couldn’t climb over, so Mom and I resumed our cocktail banter. After a few minutes, we heard the front door slam as Dad escaped again into the night.

Dad lost his business in 1972. Unable to find work in his late-fifties, he and Mom lived off an inheritance from her family for the rest of their lives.

By the early 1980’s, Mom was confined to her bed with a progressive spinal-cerebral disorder. Dad stayed home most nights, but he occasionally performed his vanishing act and left her alone in an upstairs bedroom.

During my obligatory weekend phone call from San Francisco, Mom never missed an opportunity to let me know about her abandonment.

“He leaves me alone in the house until all hours!”

Once, in a tone laden with subtext, she added:

“He brings strange men home from the bar. I don’t know what’s going on down there!”

She paused, waiting for me to feel sorry for her. Without thinking, I asked a big question.

“What are you getting at Mom? Do you think he’s …?”

She choked me off.

“I don’t know what to think! I’m just so scared and alone!”

I should have known that she wasn’t looking for insight. She wanted pity. It was the emotion that she craved after giving up on love.

I also didn’t know what to think, but her words chafed my psyche like a bur in a wool sock grating against a bloody ankle.

The incident that really got me wondering took place during another phone call in the mid-1980’s. When Dad picked up, I waited for his usual “Hold on. I’ll get your mother,” but he had something else on his mind.

“Listen, I’ve been thinking I’d like to come visit you in San Francisco.”

I took a moment to let the idea penetrate.

“Okaaay, but what about Mom?” I asked.

“She’s all for it. God knows I need a vacation!”

Something didn’t feel right. In all the years that I’d lived in San Francisco, he hadn’t shown any interest in visiting. Why now?

“I’ll only be gone a week,” he continued. “Don’t worry, we’ll get full-time help, no problem.”

As my mind grappled with the idea of injecting my alcoholic father into my California life, I had to re-state a few facts, starting with my two roommates in AA.

“You know we’re all sober in this apartment and there’s no drinking here.”

Silence.

“Also, you know that we’re all gay ….”

“Yeah, I know that,” he interjected.

I contemplated the push-buttons on the phone.

“Look Dad, I’d really like for you to stay here, but maybe you’d be more comfortable in a motel down the street.”

“Let me think about it,” he replied, then put Mom on the phone.

He called back the next Sunday.

“I still want to come but I think I’ll stay in that motel. I like to have a few beers at night.”

I imagined him packing a bottle of vodka and his blue glass.

“Okay, that’s probably the best thing.” I replied.

I wasn’t hurt that he chose booze over staying with me. I was relieved.

Then he uttered the words that I never saw coming.

“About the gay thing, I know more about it than you think, but I’ll talk to you when I get there.”

Before I could say anything, he called upstairs and Mom hopped on the line.

“Isn’t it exciting? I wish I could come too, but I’m just so sick!” she cried.

I listened to her litany of woes as Dad’s words drifted to the back of my mind. By the time I hung up and got on with my day, I decided not to count on him coming to San Francisco.

But I couldn’t shake his comment about “knowing more about the gay thing.” When I searched my memory for some clue to its meaning, the only thing I came up with was one of his war stories about how, as an officer, he had shown training films about the ravages of syphilis to enlisted men. Maybe “knowing more about the gay thing” was just these warnings about the dangers of consorting with prostitutes and “queers.”

Or was Dad going to tell me that he had acted out sexually with men?

These thoughts lined up in my head like beads on an abacus, a device that I never mastered. They formed patterns, but they didn’t add up to much, so I just let them go. I figured that we’d hash it out if he ever made it to California.

Within a few weeks, he was too sick to go anywhere.

While Dad was alive, he never asked about my personal life and I didn’t volunteer much. If I had a boyfriend, I volunteered that tidbit, but that was usually as far as it went. When the AIDS epidemic hit, I knew that my parents cared, but when I told them that I was losing my lover, they could only mutter a few sympathetic words for a stranger.

After he died in January of 1989, his words about “the gay thing” haunted me, so I picked up the phone and called Mom to see if he had told her something. I started slowly:

“Dad never said much about my being gay, so I always wondered how you two came to terms with it. I figured that you just talked it out and came to some sort of peace ...”

“Oh no, we never talked about it,” she interrupted. “And I think your father had a lot more trouble with it.”

I should have known that they never talked. Buried for years inside of their invisible bunkers within the same house, their marriage had devolved into an armed standoff. Their inability to communicate was due to what AA calls “the bondage of self" and they both had it in spades.

Although Mom didn’t have any answers, she surprised me when she said that Dad was troubled by my sexuality. He never criticized me for being gay and he never went out of his way to trash “queers,” as a matter of fact he seemed to genuinely like Mom’s gay friends. A strident racist, he never missed a chance to toss the N-word around, but where homosexuals were concerned, he left that ball on the ground.

When I resolved to put the whole thing out of my mind and just move on, I expected to exclude Dad from my future as handily as I had banished him from my youth. But sometimes his voice calls out inside of me. It draws me back to the edge of the dark abyss that was always between us and I peer once again into its depths, searching for the truth that my father couldn’t tell me.

nw

POST SCRIPT: If Dad had told me about any gay experiences in the war, I’d have been glad that he got some comfort during those horrible times. If he’d said that he was still having sex with men, and he wanted me to keep it a secret, it would have put me in an awkward position.

I detested the hypocrisy of the closet. After all Barbie went through, didn’t she deserve to know the truth? And what about all those loveless years with Mom?

When I needed him most as a father, he was worth about as much to me as a three-dollar bill. But I would have kept his secret if it finally formed a bond between us. I had waited a long time behind my door for Dad to notice me. If he had knocked just once, I would have done anything to let him in.